Mezzotint

Mezzotint is a printmaking technique that originated in the 17th century and is known for its ability to produce rich, tonal images with a distinctive velvety texture. The word “mezzotint” is derived from the Italian “mezzo-tinto,” a word, meaning “half-tinted,” reflecting the technique’s emphasis on tonal gradations.

The technique is known for its meticulous and time-consuming printing process. The key to this technique lies in creating a tonal image through a roughened surface, which contrasts with traditional etching or engraving methods.

The process relies on soft gradations in light and shade, rather than lines, to form images. The images formed through mezzotint emerge from a process starting with darkness and evolving into light.

History

The mezzotint printmaking technique renowned for its tonal richness, originated in the 17th century. It was developed by Ludwig von Siegen, a German soldier and artist, but it was the Dutch artist Prince Rupert of the Rhine who refined and popularized the technique around 1642.

The printing technique gained significant popularity in the 18th century, becoming a favoured medium for reproducing artistic prints and portraits. Its ability to capture subtle light and shadow made it particularly appealing to artists and printmakers of the time.

Mezzotint art history is marked by its evolution from a novel invention to a widely adopted printing technique, contributing to the world of visual arts during the Baroque and Rococo periods. Over the centuries, artists have continued to explore and experiment with the printing process, ensuring its enduring presence in the realm of printmaking.

Wallerant Vaillant, a Dutch painter and one-time assistant to Prince Rupert of the Rhine, picked up the technique and went on to become the first professional engraver of the technique. Numerous other Dutch artists, such as Abraham Blooteling, Jan van Somer, Pieter Schenk, Jacob Gole, and Gerard Valck, came to work in London and shared their knowledge of the mezzotint technique with British publishers and artists.

Alexander Browne and Richard Thompson played a critical role in promulgating mezzotint prints in England. They were the first to publish descriptions of the technique in English and also printed large runs with distinctive quality.

Mezzotint Process

The printing process typically involves the following steps:

Rocking the Plate with Mezzotint Rocker

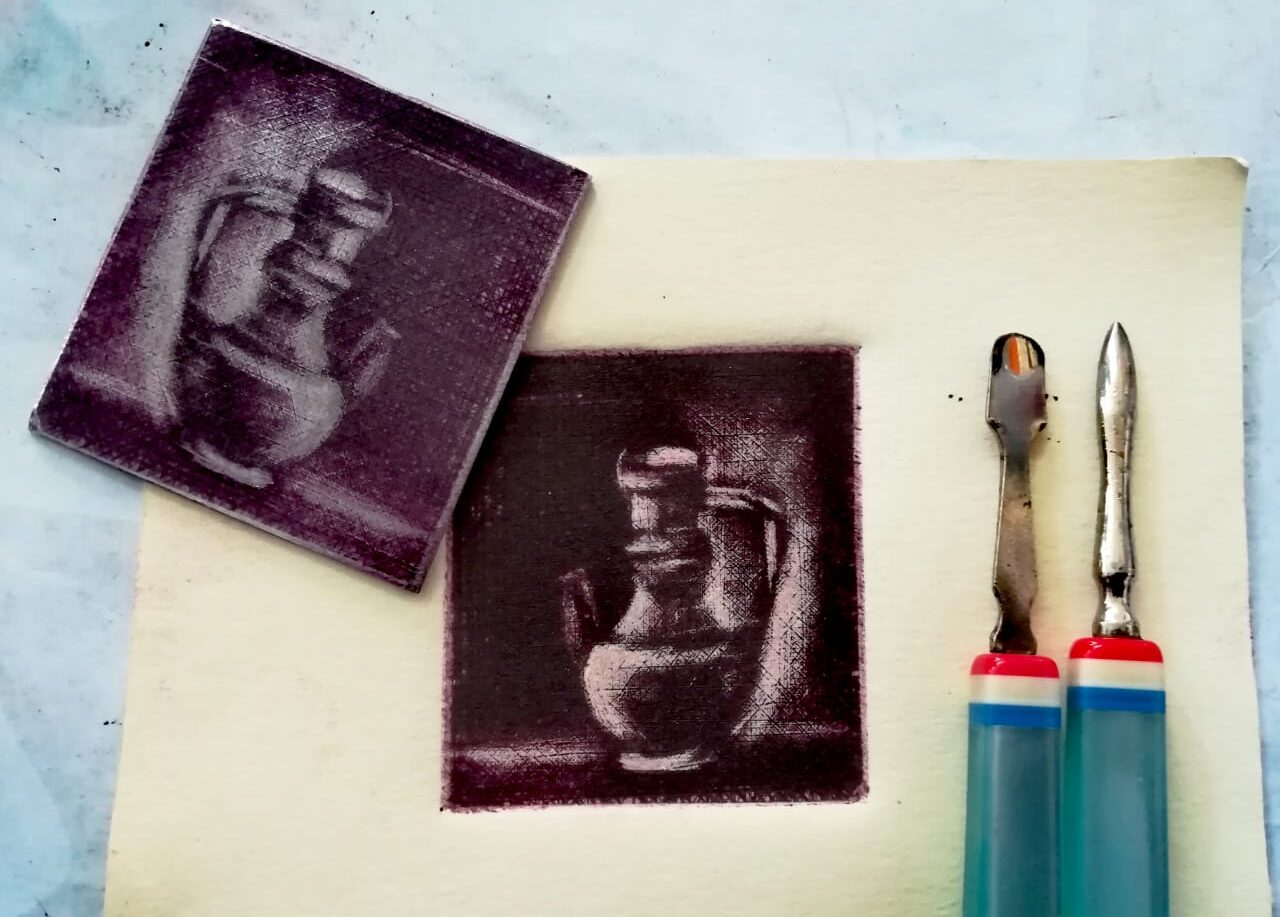

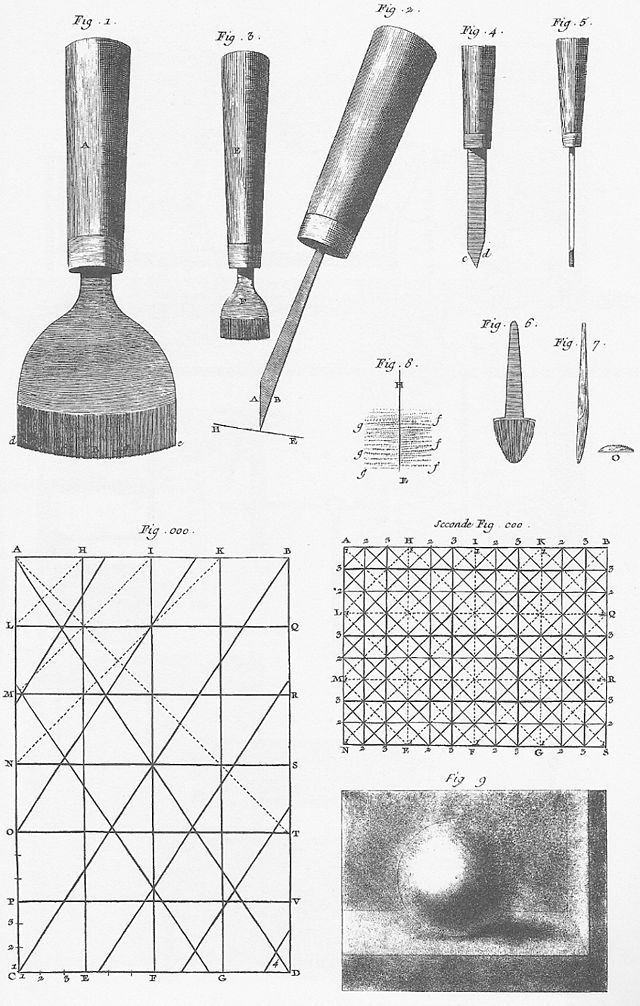

The metal printing plate, usually copper, is rocked with tools called a “mezzotint rocker.” This tool features a serrated edge that creates a fine network of pits on the plate’s surface.

Smoothing and Scraping

The artist then smoothens certain areas of the plate using scrapers and burnishers. This step allows for a wide range of tonal values, with the smoothed areas holding less ink and appearing lighter in the final print.

Etching and Engraving

Additional details can be added by etching or engraving specific areas of the plate. This step enhances the overall precision and clarity of the image.

Inking and Printing

Once the plate is prepared, it is inked, and excess ink is wiped away, leaving ink only in the pits and grooves. The plate is then pressed onto paper through an etching press machine to transfer the image.

Mezzotint Techniques

Artists employ various techniques to achieve diverse visual effects. Some notable techniques include:

Drypoint Mezzotint

Combining the technique with drypoint, artists create prints with a softer appearance, incorporating the delicacy of drypoint lines.

Scrambling

This technique involves selectively roughening areas of the copper plate with a rocker to achieve textured effects or to suggest shadows and highlights.

Roulette

By using a roulette, a spiked wheel artists can create a more even distribution of pits on the plate, resulting in smoother gradients.

A mezzotint art emerges from darkness into light. The process requires great care since the burr of a plate makes it more fragile than those used in other printmaking techniques. Because the plate’s roughened surface deteriorates rapidly from repeated printing, each plate will render only a small number of truly first-rate impressions. The plate can be reworked yielding successive “states” of the print, but such reworking historically has not always been expert, and connoisseurs have come to favour early proofs, pulled when the original burr is fresh.